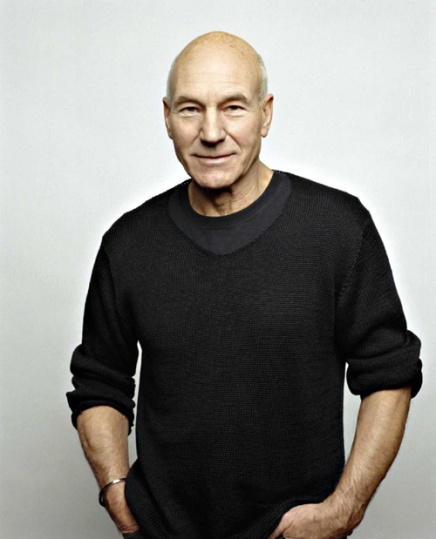

I came across this very powerfully written article by actor Patrick Stewart written for UK newspaper The Guardian in 2009.

As a child, the actor regularly saw his father hit his mother. In his own words he describes how the horrors of his childhood remained with him in his adult life.

“My father was, in many ways, a man of discipline, organisation and charisma – a regimental sergeant major no less. One of the very last men to be evacuated from Dunkirk, his third stripe was chalked on to his uniform by an officer when no more senior NCOs were left alive. Parachuted into Crete and Italy, both times under fire, he fought at Monte Casino and was twice mentioned in dispatches. A fellow soldier once told me, “When your father marches on to the parade ground, the birds in the trees stop singing.”

In civilian life it was a different story. He was an angry, unhappy and frustrated man who was not able to control his emotions or his hands. As a child I witnessed his repeated violence against my mother, and the terror and misery he caused was such that, if I felt I could have succeeded, I would have killed him. If my mother had attempted it, I would have held him down. For those who struggle to comprehend these feelings in a child, imagine living in an environment of emotional unpredictability, danger and humiliation week after week, year after year, from the age of seven. My childish instinct was to protect my mother, but the man hurting her was my father, whom I respected, admired and feared.

From Monday morning to Friday tea time he worked as a semi-skilled labourer, and was diligent and sober. Often funny and charming, he was always rich in the personal stories of warfare and adventure that thrilled me. But come Friday night, after the pubs closed, we awaited his return with trepidation. I would be in bed but not asleep. I could never sleep until he did; while he was awake we were all at risk. Instead, I would listen for his voice, singing, as he walked home. Certain songs were reassuring: I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen; I’ll Walk Beside You . . . But army songs were not a good sign. And worst of all was silence. When I could only hear footsteps it was the signal to be super-alert.

Our house was small, and when you grow up with domestic violence in a confined space you learn to gauge, very precisely, the temperature of situations. I knew exactly when the shouting was done and a hand was about to be raised – I also knew exactly when to insert a small body between the fist and her face, a skill no child should ever have to learn. Curiously, I never felt fear for myself and he never struck me, an odd moral imposition that would not allow him to strike a child. The situation was barely tolerable: I witnessed terrible things, which I knew were wrong, but there was nowhere to go for help. Worse, there were those who condoned the abuse. I heard police or ambulancemen, standing in our house, say, “She must have provoked him,” or, “Mrs Stewart, it takes two to make a fight.” They had no idea. The truth is my mother did nothing to deserve the violence she endured. She did not provoke my father, and even if she had, violence is an unacceptable way of dealing with conflict. Violence is a choice a man makes and he alone is responsible for it.

No one came to help. No adult stepped in and took charge. I needed someone else to take over and tell me everything was going to be all right and that it wasn’t my fault. I wanted the anger to go away and, while it stayed, I felt responsible. The sense of guilt and loneliness provoked by domestic violence is tainting – and lasting. No one came, but everyone knew. Our small houses were close together. Every Monday morning I walked to school with my head down, praying that I would not encounter a neighbour or school friend who had heard the weekend’s rows. I felt ashamed.

Very occasionally one person would come to our aid – Mrs Dixon, our next-door neighbour, the only person who would stand up to my father. She would throw open the door and stand before him, bosom bursting and her mighty weaver’s forearm raised in his face. “Come on, Alf Stewart,” she would say, “have a go at me.” He never did. He calmed down and went to bed. Now I wish I could take Lizzie Dixon’s big hand in mine and thank her.

Such experiences are destructive. In my adult life I have struggled to overcome the bad lessons of my father’s behaviour, this corrosive example of male irresponsibility. But the most oppressive aspect of these experiences was the loneliness. Very recently, during a falling-out with my girlfriend, I felt again as though I were shut out and alone, not heard or understood. I was neither, but it was such a familiar isolation that it was almost a comfort and consolation.

I managed to find my own refuge in acting. The stage was a far safer place for me than anything I had to live through at home – it offered escape. I could be someone else, in another place, in another time. However, whenever the role called for anger, fury, or the expression of murderous impulses, I was always afraid of what I might unleash if I surrendered myself to those feelings. It was not until 1981, when the director Ronald Eyre asked me to play the psychotic Leontes in The Winter’s Tale, that the breakthrough came.

He quietly told me that the play would only work if I gave myself over, completely and totally, to the delusions, madness and murderousness of this man. “If you do that,” Ron said, “I will be at your side. I will be available to you 24 hours a day.” From that time forward I was never again afraid of my feelings on stage.

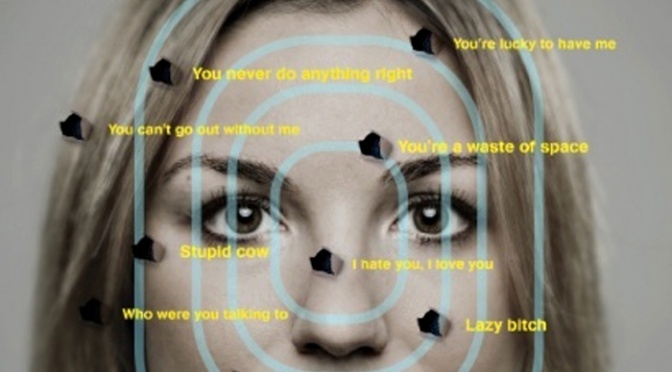

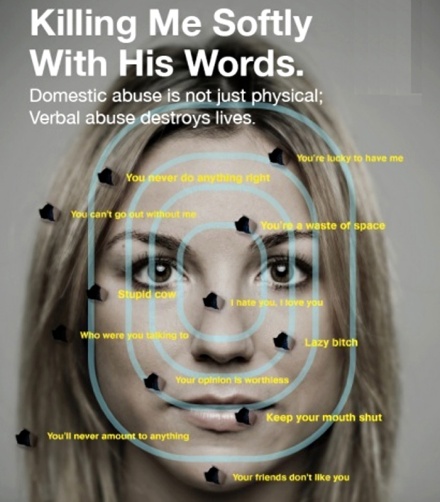

The truth is that domestic violence touches many of us. It is very possible that someone you know – a friend, sister, daughter or colleague – is experiencing abuse. One in four women will experience domestic violence at some point in her lifetime. And every week two women are killed by a current or former partner in England and Wales, and 10 women take their own lives as the only way they know how to escape a violent partner. You are almost certainly paying for it. Domestic violence costs around £26bn a year in medical, legal and housing costs.

This violence is not a private matter. Behind closed doors it is shielded and hidden and it only intensifies. It is protected by silence – everyone’s silence. Which is why, in 2007, I became patron of Refuge, the national domestic violence charity. Every day the organisation supports more than 1,000 women and children through its national network of refuges and services. At Refuge, women and children are given psychological support to help them overcome the trauma of abuse. A team of independent legal advocates are on hand to protect women at high risk of violence through the legal process.

Thanks to Refuge’s tireless campaigning, attitudes have changed. Police tactics have improved and most men are no longer able to get away with beating women. Yet the statistics still make for grim reading. More than two thirds of the residents in Refuge’s network of refuges are children. I cannot express how sad – and angry – it makes me to think that we still cannot ensure the safety of women and children in their own homes.

Most people find the idea of violence against women – and sometimes, though rarely, against men – abhorrent, but do nothing to challenge it. More women and children, just like my mother and me, will continue to experience domestic violence unless we all speak out against it”.

Photo courtesy of Collect: Patrick Stewart as a baby with his mother Gladys.